Glory

-or-

Razor Sharp Bivalves

PHOTOGRAPHING PRO CLIMBER Kevin Jorgeson

“…a sport that puts climbers high above a safe height with no ropes and a high chance of falling.”

When I moved to Sonoma County, CA some 8 years ago, I felt a little like I was unplugging from my roots in the outdoor adventure space. But I quickly discovered that this county is home to some of the most wild and visionary adventure athletes I’ve ever known. It was here that I finally found a partner to climb El Cap with, rode my first bike-camping tour, and met pro-climber Kevin Jorgeson.

Figuring out adventure sporting in Sonoma County took me some time - in part because it requires vision, imagination, and research to find the goodies.

This is still a land of firsts for many adventure sports and Kevin, who is known for his visionary pursuit of highball bouldering (a sport that puts climbers high above a safe height with no ropes and a high chance of falling), invited me along to photograph a new project far out on the rugged Sonoma Coast that he’d been developing.

“…local weather patterns that can generate deadly sneaker waves.”

We arrived at a massive boulder, somewhat bigger than my house, which had shorn free from the adjacent coastal cliff and tumbled down the hill. The route he’s spotted, now named Full Circle, starts in the intertidal zone-meaning that the bottom half of the route is often wet, and a successful climb requires knowledge not only of tide charts, but also of local weather patterns that can generate deadly sneaker waves.

I joined Kevin on a scouting mission to explore the project and assess ocean conditions. While he made a few attempts on the problem with a rope to secure him from falls, I calculated sun angles over the coming months to try to co-ordinate the best possible time to photograph the towering boulder.

The project wouldn’t be considered complete until he made a true “send”, which in this case meant ditching the rope and harness and facing a fall of up to 30’ onto jagged rocks and razor-sharp mussels. So we would certainly be returning when conditions were favorable.

“…’send’, which in this case meant ditching the rope and harness and facing a fall of up to 30’ onto jagged rocks and razor-sharp mussels.”

Finally, a day arrived when Kevin felt the conditions were right (and the sunlight was raking across the stone, just so).

With an athletic shoot like this where the danger is SO HIGH, there’s typically just one opportunity to get “the shot”. I knew though that I wanted to get both a horizontal and vertical composition at the same peak moment of action.

To do this I synced 2 cameras to the same shutter: one on a tripod composed for the horizontal image, and the other in my hands for the vertical so that I could roam around a little. Every time I pressed the shutter on my handheld camera, the second camera on the tripod took a picture at the same time.

I love the little spotter in the yellow jacket far below, fruitlessly holding their hands up - as though there’s any hope that they could help should Kevin fall.

What a great sport :)

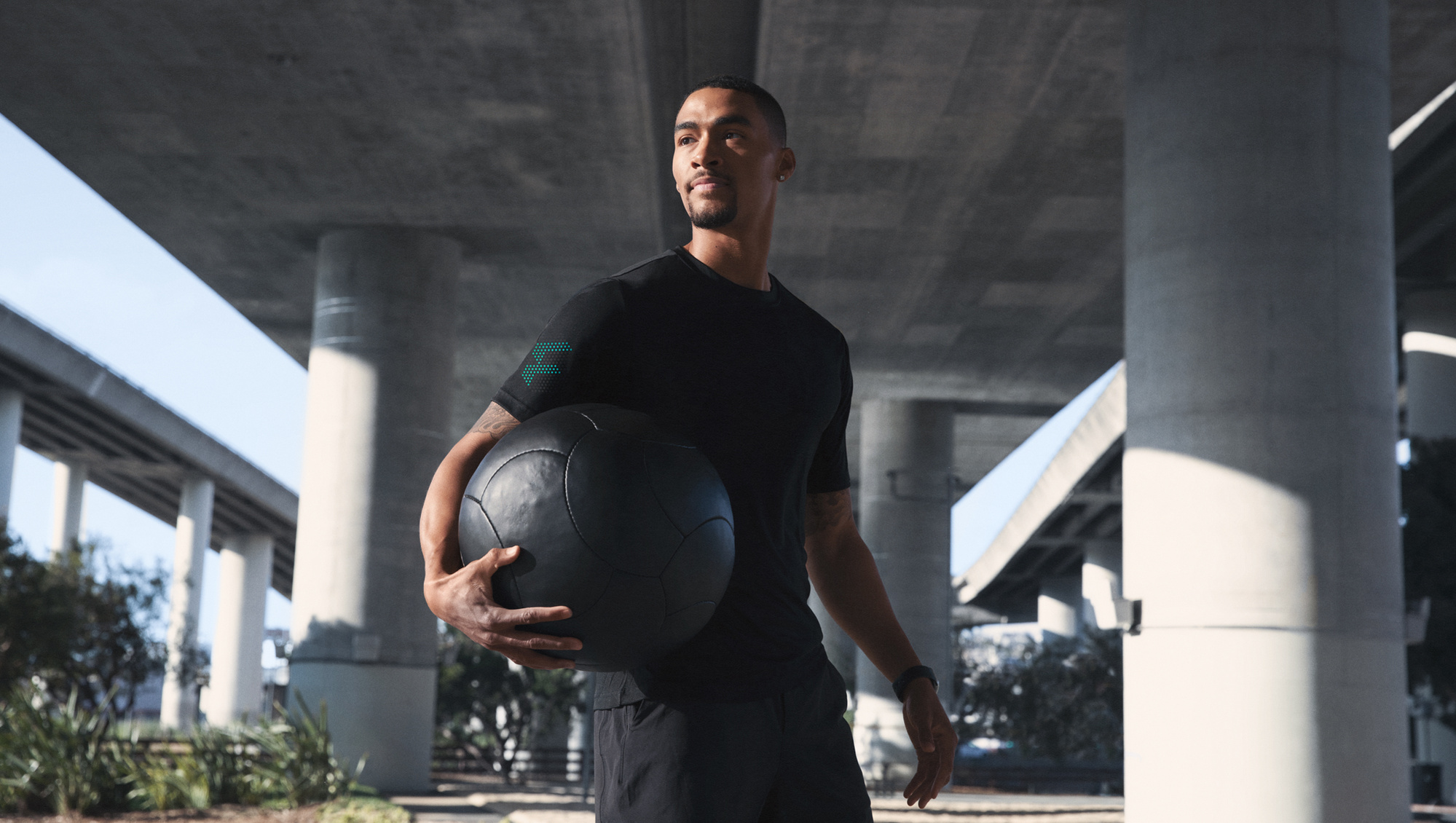

Future.fit, a fitness tech company based in San Francisco, recently launched their first branded apparel and accessory collection to compliment their personal trainer app service. The art direction called for the implication of fitness or workout routine so that we could draw more attention to the apparel and the wellness lifestyle the brand promotes.

I had really wanted to find a rooftop basketball court location for this shoot with a view of a city skyline but the great option in San Francisco’s Chinatown (featured in the film Pursuit of Happyness) is currently unavailable to the public (or private commercial photographers for that matter) thanks in part to COVID restrictions.

In a subsequent search of the city we discovered this gem of a public park built right under a major interchange overpass. I loved the way the morning light cut hard lines through the urban architecture and how those lines are softened by park foliage. It’s the sort of architecture and urban planning that’s speaks to a hopeful future.

It took scouting a number of spaces across SF to finally settle on this one…frankly the dynamic shifting of light and shadow in this space made it a tricky one for the shoot we had sketched out, but with some on-point help and great direction we chased those shadow lines around and came out with a great set of images.

On a bit of a tangent, one of my ongoing personal projects is about architecture, conservation, and restorative landscaping (I’ll share some of that work soon). Some part of me wanted to sneak in a hint of that theme while still getting the nearly sci-fi cinematic look of large scale urban infrastructure. This spot in San Francisco’s east shores is really in incredible and hopeful use of urban space.

Client: Future.fit

Creative Direction: Studio Iverson

Photographer: Studio Iverson / Kaare Iverson

H&M: Sarah Ashton

DT: Gary Ottonello

Assistant: Julian Arreguin

fitness

apparel

fashion

san-francisco

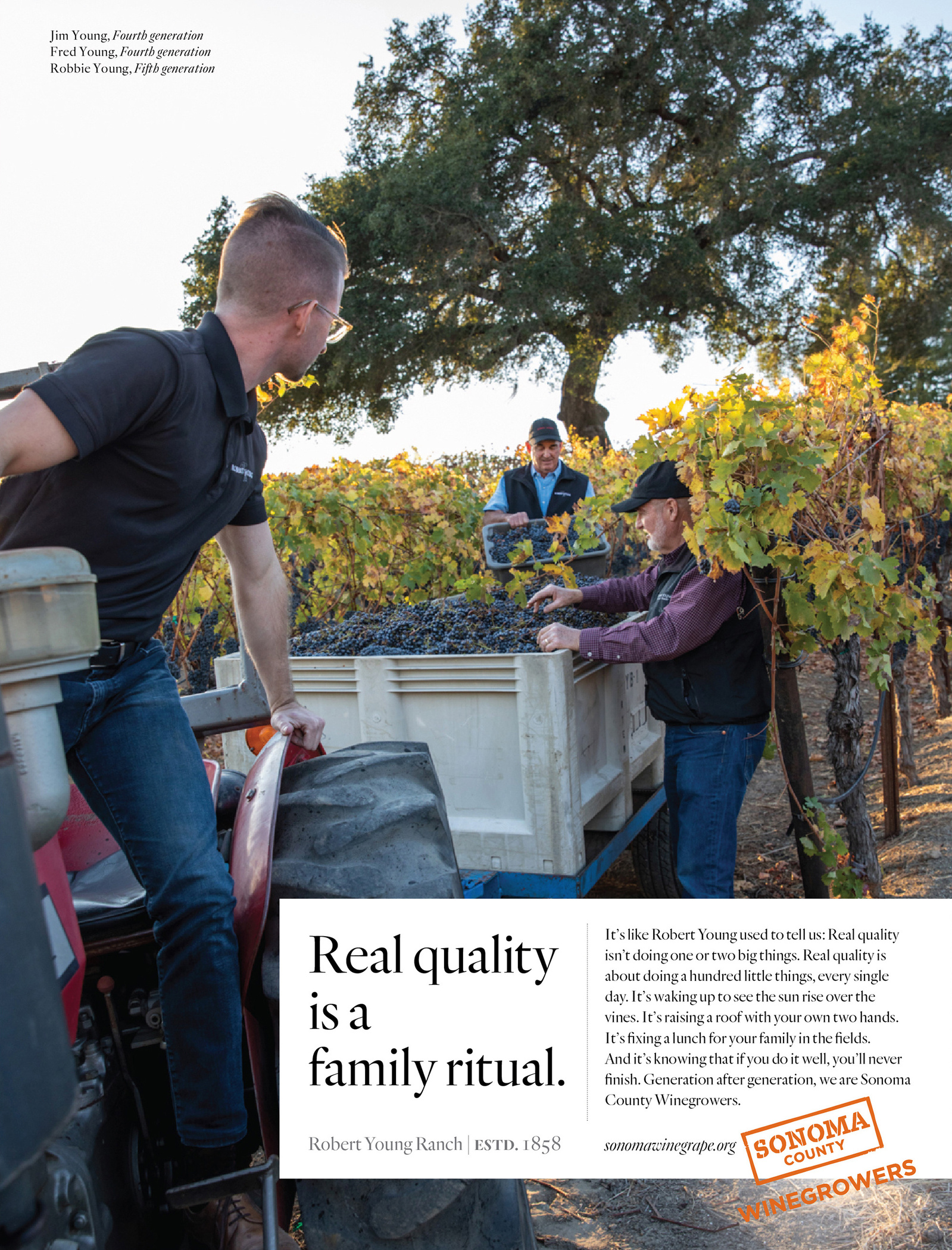

Over the last couple years I’ve been working with San Francisco based agency Siegel & Gale to produce and shoot a multi ad campaign for Sonoma County Wine Growers Association. The ad concept was to highlight multi generational families who’ve been land stewards and wine grape growers in a style appeared editorial and authentic. By working with the families directly before the shoots we were able to develop realistic vignettes based on each family’s unique history and daily experience.

I’ve really enjoyed working on this project because it exists right at the intersection of commercial and editorial photography. Working in this space is something that I’ve had a lot of experience in over the years shooting in the outdoor recreation and fitness industry, but what was uniquely lovely in this job was that the process was so fully collaborative with the subjects - we didn’t push for anything other than what felt like absolute honesty and reality from them and I think that really shines through in the work.

Being able to set reality into motion, but have enough production oversight to direct and block and light scenes within that reality has been a splendid experience. Despite the extensive pre-production and lighting magic, each ad feels authentic.

These ads have run nationally in print publications including Food & Wine.

Siegel & Gale recently posted about their experience with the campaign on their site. You can read more about it here:

https://www.siegelgale.com/sonoma-county-winegrowers/

Cheers!